Language disclaimer: This webpage discusses topics related to weight stigma and its intersection with “obesity” and eating disorders. The content addresses language and societal attitudes that have historically medicalized and pathologized larger bodies. As such, we have placed the terms “obese” and “overweight” in quotation marks to acknowledge the harms and stigma in using these terms. In line with critical weight and fat studies, we also use the term “fat” as a neutral descriptor of size and in reclamation of the term that has historically carried harmful negative connotations. For more information on this topic, you can visit this NEDIC webpage.

Weight bias refers to harmful weight-related attitudes, beliefs, and assumptions about people based on their weight. Weight bias manifests in society through weight stigma, or the harmful social stereotyping of people based on their weight. Weight bias and stigma can lead to weight discrimination, or the inequitable and unjust treatment of people due to their weight within settings such as the workplace, healthcare facilities, educational institutions, and the media. Weight bias and stigma can also lead to internalized weight bias, which is when negative weight-related attitudes, beliefs, and assumptions become internalized and applied to oneself.

Internalized weight bias can be an independent contributor to negative physical and psychosocial outcomes, such as weight cycling, depression, and disordered eating (Prunty et al., 2022; Pearl & Puhl, 2018;Puhl & Heuer, 2010; Quinn et al., 2020). Additionally, weight bias, stigma, and discrimination can all threaten access to, as well as the quality of, healthcare, which can also have negative consequences on physical and psychosocial health (Kirk et al., 2020; Puhl & Huer, 2010)

“Obesity” and eating disorders are often discussed and addressed separately in public health practice and policy. For instance, many health promotion campaigns revolve around “anti-obesity” initiatives, and the conversations about the causes of weight gain often leave out a multitude of factors beyond individuals’ knowledge and behaviours. In reality, “obesity” and eating disorders share similar factors, which can span from individual-level influences (e.g., negative body image, disordered eating behaviours) to broader societal influences (e.g., weight stigma).

Focusing on weight within conversations about health perpetuates misconceptions about weight being a reflection of one's health status and lifestyle choices. “Obesity” and eating disorders are often addressed as unrelated concepts. While they are distinct from each other, discussions that do not consider how they are related can lead to unintended harms, like the stereotype that only people with (very) thin bodies can have eating disorders, and that those in larger bodies do not or cannot experience these conditions. At the same time, "obesity" is often mentioned in the same breath as eating disorders, implying that "obesity" is a type or reflection of disordered eating. This can lead to false assumptions about individuals in larger bodies – they must not know how to eat "normally" or must have binge eating disorder, which has led them to become the size that they are.

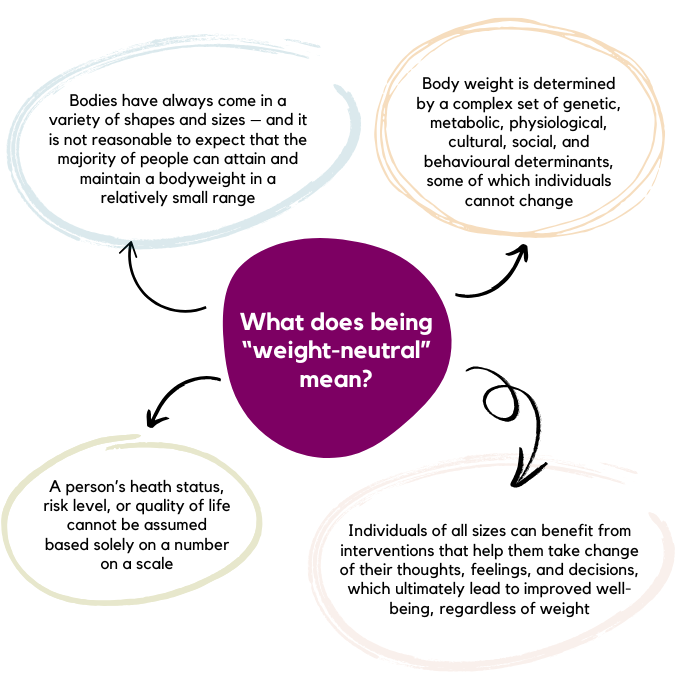

Understanding that it is not constructive to continue tethering weight to conversations about health is a necessary step towards breaking down these harmful stereotypes and promoting inclusivity of people of all shapes and sizes. Weight inclusivity involves respecting the diversity of body shapes and sizes that naturally exists, and rejecting the idealizing or pathologizing of specific weights. Weight-inclusive approaches to health, therefore, emphasize that there are many components to wellbeing, and support people to achieve health without focusing on weight. Weight-inclusive approaches also employ intersectional and trauma- and violence-informed lenses to acknowledge how weight bias, stigma, and discrimination overlap with other systems of oppression.

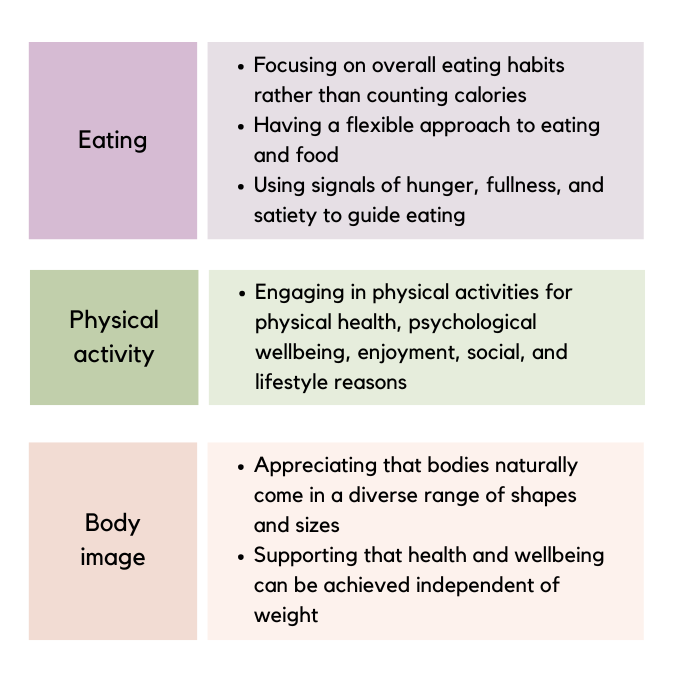

This table contains some examples of ways in which weight-inclusive approaches can be applied to messages around eating, physical activity, and body image (NEDC; Rodgers et al., 2023; Tylka et al., 2014).

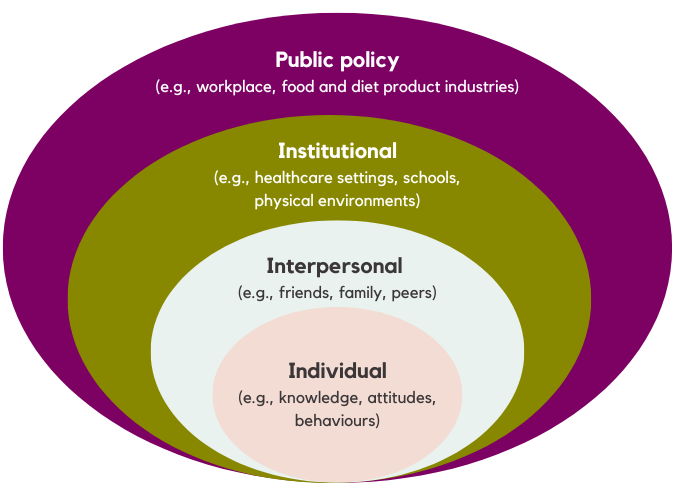

Within society, there are various levels in which weight stigma can perpetuate itself, ranging from individual-level factors to broader sociocultural influences. Some examples are outlined below. Within each level, there are different opportunities for action or self-reflection that people can take to begin to challenge weight stigma and create more weight-inclusive environments.

We present broader sociocultural influences, as well as individual-level factors, to emphasize how “no amount of change in attitudes will compensate for a health care environment that is made only for thin(ner) bodies" (Hardy, 2023)

Creating environments that protect against weight stigma and support health for all requires broad weight-inclusive public policies. Such policies prioritize respect for bodies of all shapes and sizes, and equitable access to health care resources that enable everyone to live with dignity. Some examples of weight-inclusive policy actions are described below (but note that this list is not exhaustive!)

• Advocate for weight or body size to be included as protected grounds within workplace, healthcare, and educational human rights policies.

• Ask for and/or advocate for calorie-free menus to be available in restaurants.

• Advocate for greater policy action to enhance regulation within the diet product industry, such as imposing age restrictions, taxation, moving weight-loss and muscle-building products behind the counter (Ganson et al., 2023).

The Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders (STRIPED), an advocacy group located in the United States, has created several resources and materials to support advocacy efforts related to policy and the diet product industry. These resources can help guide the development of similar resources within Canadian contexts, such as this webinar by Dr. Kyle Ganson.

• Conduct regular reviews and evaluations of human rights and mental health policies, guidelines, and programs by engaging those with expertise in weight stigma, as well as experts by lived experience.

• Reflect on what actions your workplace or institution currently takes to prevent and address weight discrimination. The National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance (NAAFA) provides a Size Diversity in Employment HR Training Guide that includes various case studies, accessibility and accommodations considerations, and additional resources that can help guide the creation of weight-inclusive workplace environments.

• Reflect on what broader policy actions can be made to support health (e.g., related to food, diet, fashion industries), as opposed to policy initiatives that focus specifically on individual behaviour change (e.g., modifying diet).

Storytelling and reclaiming narratives for systemic change

Critical media literacy and Media literacy

Equity-centered community design

Designing for collective liberation and Inclusive frameworks for collective liberation

Positioning “obesity” as a “disease” can perpetuate oppressive and stigmatizing notions about fat bodies requiring medical treatment that reduces their fatness. In healthcare settings, weight-related biases among care providers can lead them to cause harm to patients at an individual level, and more broadly to communities. Shifting away from the focus on weight and weight loss in discussions about health and wellbeing is a crucial step towards eliminating weight stigma and creating weight-inclusive healthcare settings.

Untethering weight from health can look and be defined differently for different people. Take a look at some approaches below:

• Lean into conversations about weight with curiosity.

• Remember that service users in fat bodies will likely have a history of being mistreated because of their weight or body size (trauma-informed lens); avoidance, shame, guilt, and suspicion are normal responses given this.

• Eliminating fat pathologizing language from clinical practice (i.e., overweight, obese). These terms do harm by representing fatness as an “abnormality” and suggest that there is a “right” or “acceptable” weight for all people to strive for.

Ask patients how they want their body to be described. Make a habit of asking people about the language they use to describe their own body. Try to mirror their language.

• Keep in mind that weight is not a behaviour. Focusing on supporting patients to make health-promoting behaviour changes that align with their desires and goals, rather than on weight or weight loss, can help improve a variety of physical and psychological health outcomes, as well as strengthen provider-patient relationships (Raffoul & Williams, 2021). Weight should only be mentioned when necessary and/or the patient brings it up. If the patient has not brought it up themself, it is crucial to ask for their consent before discussing weight.

• Advocate for weight-inclusive medical equipment (e.g., blood pressure cuffs, medical gowns) and greater sensitivity regarding weigh-ins (e.g., having scales in a private room, and only mentioning weight when necessary and/or invited by the patient). This environmental checklist can help ensure that medical equipment within your institution is weight-inclusive and accessible.

• Reflect on how fatness is portrayed, how anti-obesity knowledge is reproduced, and the role of industry/pharmaceutical partners (e.g., Novo Nordisk) in medical discourse. This worksheet can serve as a tool to determine whether a medical-related news or media piece risks perpetuating weight stigma.

• If you don’t know how to proceed in a situation with a patient, acknowledge that. You can still show compassion for them while modelling imperfection, and that can mean a lot to someone.

School-based settings are often positioned as an ideal context to address healthy eating and physical activity among youth. However, healthy eating and physical activity are often framed as individual behaviours and the personal responsibility of the student to “make the right choices” within health and physical education curricula (Robertson & Scheidler-Benns, 2015). This framing can increase students’ anxieties about body weight and eating behaviours, as well as perpetuate body-based bullying and teasing, particularly since curricula often do not include content that teaches students about body diversity, body equity, body size acceptance, and weight-based bullying within discussions about healthy living (Larkin & Rice, 2005; Pinhas et al., 2013).

• Reflect on how current health and physical education curricula frame the purpose of teaching students about healthy eating and physical activity. For example, are topics of healthy lifestyles positioned in the context of weight management? Or are they articulated in a way that would help students develop sustainable, flexible, and balanced views about health and wellbeing? To what extent are topics such as body diversity and body-based bullying included within discussions about healthy living?

• Some curriculum-based activities can lead to unintended harms related to eating disorders and body image concerns. Consider the following activities that should be avoided within school settings (Yager, 2024), and how they could be replaced with body- and weight-inclusive activities:

• Consider booking (or advocating for) a professional development session on weight-inclusive ways to talk about eating, physical activity, body image, and mental health. As one option, NEDIC offers workshops on these topics.

The ways in which physical and built environments are set up can also be exclusionary and contribute to weight stigma. This can range from the structures of and within physical spaces (Brewis et al., 2016; Tylka et al., 2014) to content and images within health promotion messaging (Puhl et al., 2013). Removing stigmatizing cues within public spaces is essential to creating environments that are accessible and inclusive for all bodies (Brewis et al., 2016).

• Advocate for seating/furniture and room arrangements that accommodate all bodies (e.g., wide chairs without armrests, wheelchair access).

• Be aware of mirrors and reflective surfaces – they might be distracting.

• Ensure health messaging (e.g., programs, campaigns, resources, social media) do not focus on weight.

• Ensure images of people in flyers, brochures, handouts, website, slideshows include a diverse array of bodies

• Think about some of the spaces and settings in which you go about your activities of daily living. How are they accommodating – or not? accommodating of body diversity? What messages are being sent about health and weight? What would you change to create a more weight-inclusive environment?

Weight stigma can be reinforced through comments about bodies and weight during everyday interactions with people such as family members, friends, coworkers, and even strangers. One study found that over a two-week period, participants experienced an average of 11 instances of weight stigma during their everyday activities (Vartanian et al., 2014). Interpersonal weight stigma can also disproportionately impact people with intersecting identities (Sonneville et al., 2024). By challenging weight stigma when we see or hear it, we help create environments where nobody feels shame for the body in which they live.

• Lean into conversations about weight with curiosity.

• Remember that service users will likely have a history of being mistreated because of their weight or body size (trauma-informed lens); avoidance, shame, guilt, and suspicion are normal responses given this.

• If you don’t know how to proceed in a situation with a patient, acknowledge that. You can still show compassion for them while modelling imperfection, and that can mean a lot to someone.

• Create space for humanizing and empathy-inducing interactions – this is important for challenging weight stigma (Fox et al., 2020). Here are some ways to navigate conversations about bodies and food:

• Ask for consent before engaging in diet- or negative body-talk with another person, in case they themself are experiencing disordered thoughts related to eating or body image. Such talk may worsen those thoughts. If you need space to process difficult body-related thoughts with trusted friends of family members, ask permission first.

• Interrupt unsolicited weight-loss advice when you hear it. Some options to consider:

Society often frames health and weight as a personal/individual choice or responsibility. However, this individualistic approach reduces the complexity of factors that impact health and can contribute to stigmatizing anti-fat attitudes. Eliminating fatphobia and weight stigma requires us to rethink the very notion of health itself, who gets to define it, and what it means to provide “care” for “health.” Reflecting on our own knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours surrounding health and healthy living can help support shifts toward conceptualizations of health that do not revolve around weight and personal responsibility.

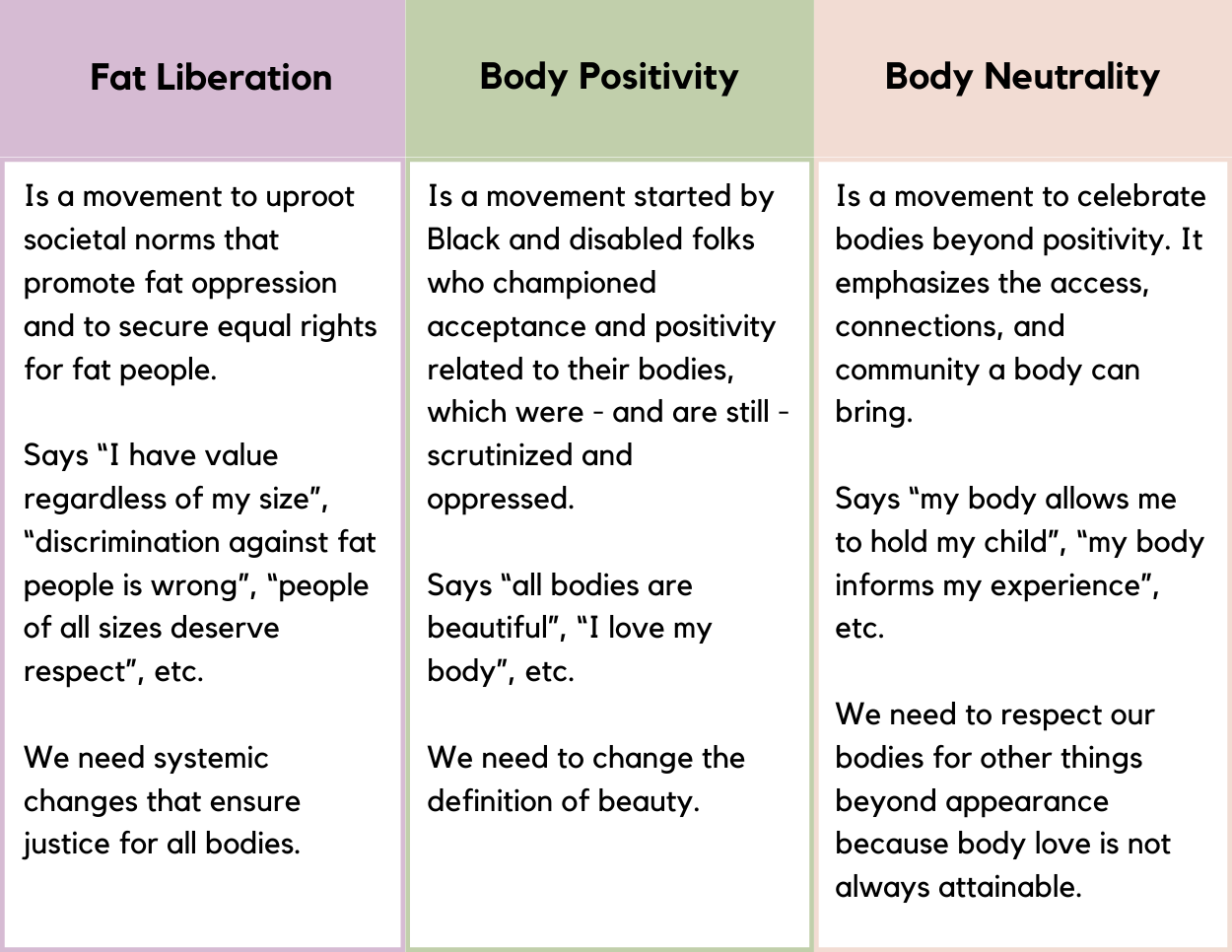

• Learn more about body liberation, body positivity, and body neutral frameworks; advocate to receive more learning opportunities like this by booking presenters who identify with these frameworks to see how you can incorporate this into your work.

• Notice how you feel when you say the word fat. What, if anything, does that word bring up for you? (Gordon, 2023) The Fat Attitudes Assessment Toolkit (Cain et al., 2022) was developed to capture the nuance and complexity of attitudes surrounding fatness. The toolkit contains various items related to topics such as size acceptance, fat activism, and critical health that can serve as a tool for further self-reflection about our attitudes, thoughts, and feelings about fatness.

• Notice when and how you describe other people’s body size. Is their size relevant to the discussion? Why or why not? (Gordon, 2023)

• Keep in mind that weight is influenced by a complex range of factors, including many factors that are outside of personal control (Swami et al., 2023; Talumaa et al., 2022). When you think about factors that impact weight, which of the factors below come most often to mind?